By Claire Zillman

@clairezillman

OCTOBER 10, 2015, 9:00 AM EDT

In the wake of the unrest provoked by the death of Freddie Gray, Baltimore’s elected officials and small businesses are pulling together to give the city’s reputation a makeover.

Baltimore couldn’t ask for a better salesman than Robert Wallace. The CEO of energy engineering and technical services consulting firm Bithenergy, Inc., grew up in the city. He attended Baltimore Polytechnic Institute, a public high school, before enrolling in the University of Pennsylvania and later Dartmouth and has launched three companies including Bithenergy, all of which are located in the city.

But since protests following the death of Freddie Gray engulfed the city in April, he’s run into a bit of trouble with his pitch.

Bithenergy’s headquarters were in the direct path of the protestors, but it was left untouched. “There was very minimal impact there,” he says. “What the protests have impacted is the image of the city.”

Wallace told Fortune that he’s having trouble recruiting new talent. “If I had an opening [before the protests] and I interviewed 10 people I may have had three or four interested in taking the job ” he says. Now, despite his hard sell—”There are concerts right outside our office and restaurants and entertainment venues,” he says—that number is down to one or two.

“As a city, we have to work on overcoming that,” he says.

Despite those challenges, Bithenergy is thriving. The company—which has installed and maintained more than 20 solar energy systems, amounting to more than 33 megawatts of solar energy in the Northeast and Mid-Atlantic Maryland, Virginia, Massachusetts, and Pennsylvania—is No. 1 on Fortune‘s 2015 Inner City 100 list, a ranking by the Initiative for a Competitive Inner Cityof the fastest growing companies in urban areas. With revenue of $7,283,800 in 2014, Bithenergy reported a 2,973% five-year growth rate. It’s one of four Baltimore-based companies on this year’s list. Brand agency Planit, Inc., events company P.W. Feats, Inc., and web development firm SmartLogic also made the cut.

Fast-growing companies like Bithenergy are prized commodities in every city, but they are especially cherished in Baltimore, a city that erupted in protests this spring following the death of 25-year-old Freddie Gray, an African American man, who died in April from spinal cord injuries that he sustained while in police custody. The Maryland governor declared a state of emergency during protests in the wake of Gray’s death, and businesses suffered $9 million worth of property damage as long-simmering tensions in Baltimore’s impoverished neighborhoods related to structural racism, police brutality, and lack of education and economic opportunities boiled over.

Following such a high-profile incident, you’d expect job hunters to be wary of Baltimore, as Bithenergy’s Wallace describes. But William Cole, president and CEO of the Baltimore Development Corporation, insists that, when the city as a whole is considered, the “exact opposite” has been the case. The city has received “more inquiries from companies interested in growing or relocating here” and major construction projects are “moving faster now than they were before.”

Before and after the Freddie Gray-related protests, several notable companies have moved to Baltimore or struck deals that reiterate their desire to stay. Danish jeweler Pandora moved its headquarters, along with 250 employees, to the city from the nearby suburb of Columbia, Md. early this year. Under Armour CEO Kevin Plank, whose company is based in Baltimore, has snapped up real estate around the city, including a recent deal for 43 acres of waterfront property in the city’s Westport neighborhood. In March, Amazon opened a 1 million square-foot distribution center at the site of a former General Motors plant that closed in 2005. The city and state gave the e-commerce giant more than $43 million in tax incentives to lure the company—a deal that required Amazon to hire at least 1,000 people. In July, Amazon said it had hired 2,500.

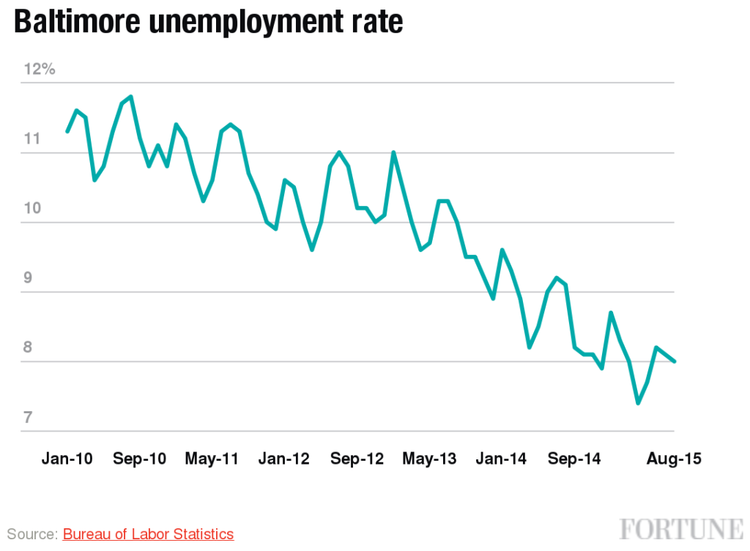

Despite those flashy deals, the city is plagued by a high unemployment rate. It was 8% in August, the most recent month data is available.

That’s 2.9 percentage points above the national average. Then again, considering that the city’s unemployment rate stood at 11.8% in August 2010, Baltimore has come a long way.

You cannot separate Baltimore’s economic problems from the mounting social challenges many of its residents face. “We still continue to struggle with the chronic problems we’ve had for decades—drugs and a [high] crime rate,” Cole says. The city reported 211 homicides in 2014, 24 fewer than the previous year’s total of 235, which had been a four-year high.

Some of the city’s local employers are trying to address these factors on their own. Johns Hopkins is the city’s largest employer and was criticized during the protests for not serving all of Baltimore. In September, Baltimore-based Johns Hopkins University and the Johns Hopkins Health System launched a program to address the city’s economic divisions by hiring local companies for its design, vendor, and construction contracts and by committing to hire at least 60 employees per year from Baltimore zip codes with high joblessness or poverty rates.

The institution is also participating in a program called Live Where You Work, which provides employees with grants of up to $36,000 to buy homes in the city and is intended to build a demand for more small businesses—restaurants, drug stores, dry cleaners—within Baltimore’s borders.

Baltimore’s city government has also tried to encourage employment with incentive programs like the one it offered Amazon. Very often, though, cities can do very little to ensure that a company hires existing local talent, Cole says. In the wake of the protests, Baltimore’s Small Business Administration announced that it would make $1 million available in loans to help businesses that had suffered physical damage during the riots and to strengthen the city’s small business community overall.

In May, Baltimore Mayor Stephanie Rawlings-Blake also launched a campaign called One Baltimore, a coalition of business, nonprofit and religious leaders to address the problems that the protests laid bare. Wallace of Bithenergy is a member of the group and, this past summer, he participated in an initiative to encourage local businesses to hire students from Baltimore’s high schools as interns. Wallace typically hires two or three interns for paid summer positions; this year he hired five.

“Businesses like ours are so critical to the survival of an urban center,” Wallace says. “If we can expose these young people to potential opportunities, it connects the dots between the choices they make today and their quality of life down the road. If we can connect those dots, they’ll make better choices and be much better off.”

Youths walk down a Baltimore street on April 30, 2015, during the period of unrest.